College and university records are great resources for family history research. These include yearbooks, catalogs, school newspapers, funeral programs, photographs, and documents donated by families.

Several men in my family attended Biddle University, which became Johnson C. Smith University, an HBCU in Charlotte, N.C. Biddle’s catalogs are digitized and are online at DigitalNC, and I love exploring them because they list the names of students, their hometowns, and their majors. I often get side-tracked and find myself tumbling down rabbit holes researching people who are not related to me but are possibly related to people I know. For example, the 1903-1904 catalog, includes several students from Darien, Georgia – Frank Atkins Brown, Hector Charles Miller, David Andrew Rogers, Hercules Wilson Jr., and Harry Wilson Leake. An older catalog, the 1897-1898 edition, includes Benjamin Monroe Grant of Darien.

In the back pages of the catalogs are lists of alumni, including their cities of residence after graduation and their occupations. Most graduates became ministers or teachers, but some became doctors, mail carriers, merchants, printers, farmers, brick masons, missionaries, and Pullman porters.

South Carolina native Walter I. Lewis, who graduated from Biddle University in the class of 1877, was listed as a news reporter in Jacksonville, Fla. This caught my attention.

A Google search revealed that an essay by Lewis was included in a 1902 book titled Twentieth Century Negro Literature: Or A Cyclopedia of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American Negro by 100 of America’s Greatest Negroes, edited by Daniel Wallace Culp. The book includes essays by many familiar people, including a Jacksonville native and school principal named James Weldon Johnson.

In Lewis’ essay, The Negro as a Writer, he wrote, “The writings of the Negro are full of soul. … The well nigh inexhaustible field of folk-lore of his own people is ready to be told to the world, whether in the crude dialect of the race, or in Americanized English, it matters little. It will make no difference. The English speaking people of both continents will read it if it is written by a master.”

According to Lewis’ bio in the book, he taught at a public school in Spartanburg, S.C., and at a parochial school in Tennessee, before switching to journalism. He was a field correspondent for The Florida Sentinel in Gainesville, the city editor for The Labor Union Recorder in Savannah, Georgia, and then he moved to Jacksonville, Florida, to work for The Jacksonville Advocate, The Daily American, and finally, as a reporter for The Metropolis, an evening newspaper that would become The Jacksonville Journal.

Wednesday, February 5, 2025

Prof. Walter I. Lewis, Journalist

Sunday, July 28, 2024

"The Black Pearl"

Learn more:

- Atlantic Beach. (2022). The Green Book of South Carolina. https://greenbookofsc.com/locations/atlantic-beach/

- Bush, G. W. (2016). White sand black beach: Civil rights, public space, and Miami's Virginia Key. University Press of Florida.

- Cruz, B., Berson, M., & Falls, D. (2012). Swimming not allowed: Teaching about segregated public beaches and pools. Social Studies, 103(6), 252-259.

- Gibson, J. (2015). Atlantic Beach: Historic African-American Enclave in South Carolina. National Trust for Historica Preservation. https://savingplaces.org/stories/atlantic-beach-historic-african-american-enclave-in-south-carolina#.YkULLOhKjIU

- Oglesby, C. (2022). How black beaches were developed to combat Jim Crow segregation. Eath Curiosity. https://earthincolor.co/earth-curiosity/how-black-beaches-were-developed-to-combat-jim-crow-segregation/#:~:text=In%20the%20South%2C%20Black%20beaches,entry%20for%20people%20of%20color.

- John Skeeter's Documentary on Atlantic Beach, S.C. (2013). Prince Domoniquie on YouTube. https://youtu.be/oLb8LVV6w2o

- Karhl, A. W. (2018). Free the beaches: The story of Ned Coll and the battle for America's most exclusive shoreline. Yale University Press.

- Kahrl, A. W. (2016). The land was ours: How black beaches became white wealth in the coastal South. University of North Carolina Press.

- King, H. T. (2021). Saving American Beach: The biography of African American environmentalist MaVynee Betsh. G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers.

- Phelts, M. D. (2010). An American Beach for African Americans. University Press of Florida.

- Stephens, R. J. (2014). Atlantic Beach, South Carolina (1966- ). Black Past. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/atlantic-beach-south-carolina-1966/

- Stephenson, F. (2006). Chowan Beach: Remembering an African American resort. The History Press.

- Town of Atlantic Beach, S.C. (n.d.). http://www.townofatlanticbeachsc.com/

Friday, March 31, 2023

Rev. Dr. Katie Geneva Cannon

|

| Courtesy of the Katie Geneva Cannon Papers, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia PA |

On this last day of Women’s History Month, I honor my cousin and kindred spirit, the Rev. Dr. Katie Geneva Cannon, shown in a collage featuring a photo of her from the 1970s and one of her works of art from 2000.

Cousin Katie was the first African American woman to be ordained in the United Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the first African American woman to earn a Ph.D. at Union Theological Seminary, a renowned scholar, and a founder of the Center for Womanist Leadership. Her legacy includes many more honors and thought-provoking lectures, books, and articles.

I never met Cousin Katie in person, but we corresponded, exchanging

articles and sharing our deep admiration for our ancestor, Mary Nance Lytle, a

strong-willed courageous woman who reclaimed her children who had been sold

away during slavery.

Cousin Katie was born in Kannapolis, N.C., in 1950, and passed away in 2018. I regret I never got the chance to spend time with her and

tell her how much I admired her.

The collage above is copyrighted and is used here with permission from the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Southern Tones and Southernaires

Second from left is Cousin James "Tunesy" Fletcher (1935-2012). He was a member of the Southern Tones of Philadelphia. Back in his hometown of Lancaster, S.C., he performed with the local group, Gospel Southernaires, along with his brothers, John Fletcher and Roosevelt Fletcher, who was the lead singer.

Sunday, January 8, 2023

George Lewis Russell, Sr.

George Lewis Russell Sr., first cousin, two times removed, was the first black Assistant Chief Clerk for the U.S. House of Representatives and served in that role for more than 17 years.

He was

the son of Joseph Samuel Russell (1886-1969) and Hattie McCauley (1887-1972). He

was born in 1924 in Concord, Cabarrus County, N.C., and graduated from Logan

High School in Concord and North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro. He

served in the U.S. Navy during World War II.

Cousin George died of a heart attack in 1991. Several members of Congress paid tribute to him, including Rep. Kweisi Mfume, (D-Md.), and Rep.

Andrew Jacobs, Jr., (D-Ind.). This image from the Congressional Record is a tribute by Rep. Mervyn M.

Dymally, (D-Calif.), on Oct. 10, 1991, in the U.S. House of Representatives. It

reads:

“Mr. Speaker, I rise to pay tribute to a man that many

considered to be a Capitol Hill institution. For 17 years George Lewis Russell,

Sr., graced these hallowed halls, with a dignity and sense of dedication that

made him a friend to all that were fortunate enough to be touched by him.

“In his position as the Assistant Chief Clerk to Reporters, the

man we affectionately referred to as George literally had a front-row seat as

we conducted the Nation’s business. Yes, Mr. Speaker, when my friends on the

other side of the aisle were in the well giving speeches, that moment was

shared by George who sat directly behind whoever was speaking.

“Mr. Speaker, aside from his duties here in the House of

Representatives, George was a dedicated family man, active in his community,

his church, and the affairs of his college, North Carolina A&T State

University.

“Mr. Speaker, George Russell always went the extra mile to help

individuals seeking employment and was always encouraging to members and staff.

“Unfortunately, there will not be any statues or buildings here

on the Hill named after George Russell. However, we can all rest assured that

this noble man will never be forgotten on Capitol Hill or in his community.”

Sources:

Tribute

by Rep. Kweisi Mfume, (D-Md.), Congressional

Record, Oct. 8, 1991, p25753.

Tribute by Rep. Andrew Jacobs,

Jr., (D-Ind.), Congressional Record, Oct. 9, 1991, p26001.

Tribute

by Rep. Mervyn M. Dymally, (D-Calif.), Congressional

Record, Extensions of Remarks, Oct. 10, 1991, p26199.

Obituaries, The Baltimore Sun, Oct. 8, 1991, p38.

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Lytle School Legacies

|

| The new Lytle's Grove Rosenwald School, 1927 |

|

| Torrence-Lytle High School |

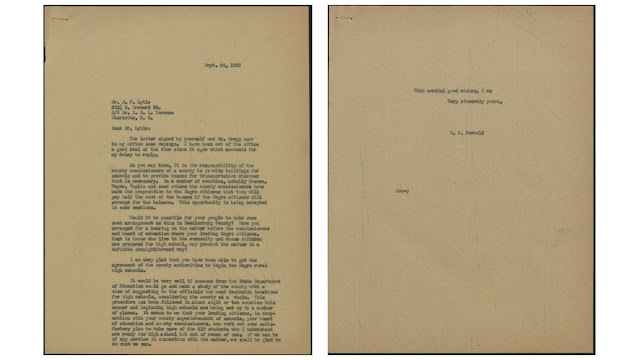

In the letter below, dated September 24, 1935, Nathan Carter Newbold, director of North Carolina's Division of Negro Education, is replying to a letter from John Frank Lytle. The letter is addressed to J.L. Lytle, in care of I.D.L. Torrence. The topic is the need for high schools and transportation in northern Mecklenburg County, to accommodate more than 200 black children who are prepared to advance but have nowhere nearby to go to school.

|

| Old Lytle's Grove School, 1927 |

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission. (n.d.). Survey and research report for the Torrence-Lytle School. http://landmarkscommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Torrence-Lytle-SR.pdf

Chris Folk Papers. (n.d.). A history note: Torrence-Lytle School. University of North Carolina at Charlotte. https://atkinsapps.charlotte.edu/node/17069

Corine Cannon Oral History, 2019. Pearl Digital Collections. Presbyterian Historical Society. https://digital.history.pcusa.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A150680

Griffith, Nancy. (2021). Rosenwald Schools: Special Davidson history column for Black History Month. News of Davidson. https://newsofdavidson.org/2021/02/18/34004/rosenwald-schools-special-davidson-history-column-for-black-history-month/

New Lytle's Grove School. State Archives of North Carolina. Department of Public Instruction: School Planning Section, School Photographs File, Box 5. https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/51479650760/in/photostream/

North Carolina Digital Collections. (n.d.). Correspondence: Rosenwald Fund, Box 4, Folder E, 1927-1928. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll13/id/1304/rec/2

North Carolina Digital Collections. (n.d.). General correspondence of the director, last name J to L, September 1935-August 1936. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll13/id/77464/rec/1

North Carolina Digital Collections. (n.d.). Report of N.C. Newbold, State Supervisor rural schools for Negroes for North Carolina, For the Month of February 1914. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll13/id/15941/rec/3

Old Lytle's Grove School. State Archives of North Carolina. Department of Public Instruction: School Planning Section, School Photographs File, Box 5. https://www.flickr.com/photos/north-carolina-state-archives/51479446819/in/photostream/

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

The Sweet Potato

I've always considered myself a child of summer, but fall has a special place in my heart. Where I live, the days are still relatively warm well into November and even December, but the nights are just chilly enough for a fire in the yard.

My husband makes the best fires, the kind of fires that make you slowly inch your chair back at first, only to scoot back up as the fire settles down to a steady simmer. A good fire brings out good stories, the true stories as well as the lies, the ones that have been somewhat embellished over time. The flames loosen the tongue and release tucked-away memories of people long gone, and the passed-down tales that they told around yard fires long extinguished.

One night on Sapelo Island, while sitting around a fire listening to lies, Cousin Tracy reached into the ashes beneath the smoldering wood and dug out a small sweet potato he had been baking. He carefully brushed it off, broke it in half, and handed a piece to me. While I normally smother my sweet potatoes in butter, cinnamon, and sugar or honey, I took a bite from the bare hot orange clump and died right there on the spot and went to heaven.

To this day, I still think about that sweet potato and how it made me feel. In each bite, I could taste the generations and savor the history and tradition, and feel the love of ancestors whose names I will never know.